what practice among the moche did the inca adapt to unify its empire

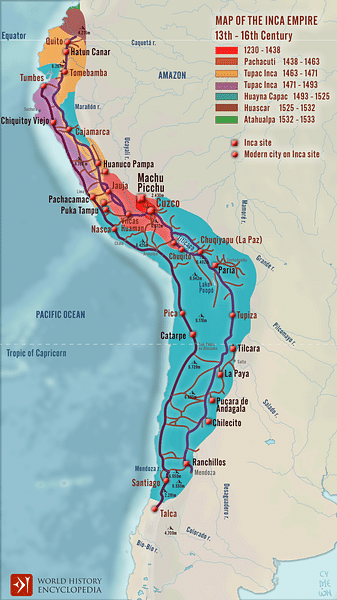

The Inca civilization flourished in ancient Republic of peru between c. 1400 and 1533 CE, and their empire somewhen extended across western South America from Quito in the north to Santiago in the s. It is the largest empire e'er seen in the Americas and the largest in the world at that fourth dimension.

Undaunted by the oft harsh Andean environment, the Incas conquered people and exploited landscapes in such diverse settings as plains, mountains, deserts, and tropical jungle. Famed for their unique fine art and architecture, they constructed finely-built and imposing buildings wherever they conquered, and their spectacular adaptation of natural landscapes with terracing, highways, and mountaintop settlements continues to impress modernistic visitors at such globe-famous sites as Machu Picchu.

Historical Overview

As with other aboriginal Americas cultures, the historical origins of the Incas are difficult to disentangle from the founding myths they themselves created. According to legend, in the get-go, the creator god Viracocha came out of the Pacific Ocean, and when he arrived at Lake Titicaca, he created the sun and all ethnic groups. These offset people were buried by the god and but afterward did they emerge from springs and rocks (sacred pacarinas) dorsum into the world. The Incas, specifically, were brought into being at Tiwanaku (Tiahuanaco) from the sun god Inti; hence, they regarded themselves as the chosen few, the 'Children of the Sunday', and the Inca ruler was Inti's representative and embodiment on world. In another version of the cosmos myth, the start Incas came from a sacred cave known equally Tampu T'oqo or 'The House of Windows', which was located at Pacariqtambo, the 'Inn of Dawn', south of Cuzco. The first pair of humans were Manco Capac (or Manqo Qhapaq) and his sister (likewise his wife) Mama Oqllu (or Ocllo). Iii more than brother-sister siblings were born, and the grouping set off together to constitute their civilization. Defeating the Chanca people with the aid of stone warriors (pururaucas), the beginning Incas finally settled in the Valley of Cuzco and Manco Capac, throwing a golden rod into the footing, established what would become the Inca majuscule, Cuzco.

40,000 Incas governed a territory with x million subjects speaking over 30 dissimilar languages.

More physical archaeological show has revealed that the first settlements in the Cuzco Valley actually date to 4500 BCE when hunter-gather communities occupied the expanse. Yet, Cuzco just became a significant centre sometime at the get-go of the Late Intermediate Catamenia (one thousand-1400 CE). A process of regional unification began from the belatedly 14th century CE, and from the early 15th century CE, with the arrival of the first bang-up Inca leader Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui ('Reverser of the World') and the defeat of the Chanca in 1438 CE, the Incas began to expand in search of plunder and product resources, first to the southward and then in all directions. They somewhen built an empire which stretched across the Andes, conquering such peoples as the Lupaka, Colla, Chimor, and Wanka civilizations along the mode. In one case established, a nationwide organization of tax and administration was instigated which consolidated the ability of Cuzco.

The ascent of the Inca Empire was spectacularly quick. First, all speakers of the Inca linguistic communication Quechua (or Runasimi) were given privileged status, and this noble class then dominated all the important roles within the empire. Thupa Inca Yupanqui (also known as Topa Inca Yupanqui), Pachacuti'due south successor from 1471 CE, is credited with having expanded the empire by a massive four,000 km (ii,500 miles). The Incas themselves called their empire Tawantinsuyo (or Tahuantinsuyu) meaning 'Land of the Four Quarters' or 'The Four Parts Together'. Cuzco was considered the navel of the globe, and radiating out were highways and sacred sighting lines (ceques) to each quarter: Chinchaysuyu (north), Antisuyu (east), Collasuyu (due south), and Cuntisuyu (due west). Spreading across ancient Republic of ecuador, Peru, northern Chile, Republic of bolivia, upland Argentina, and southern Colombia and stretching 5,500 km (iii,400 miles) north to south, 40,000 Incas governed a huge territory with some 10 one thousand thousand subjects speaking over thirty dissimilar languages.

Inca Empire - Expansion and Roads

Government & Administration

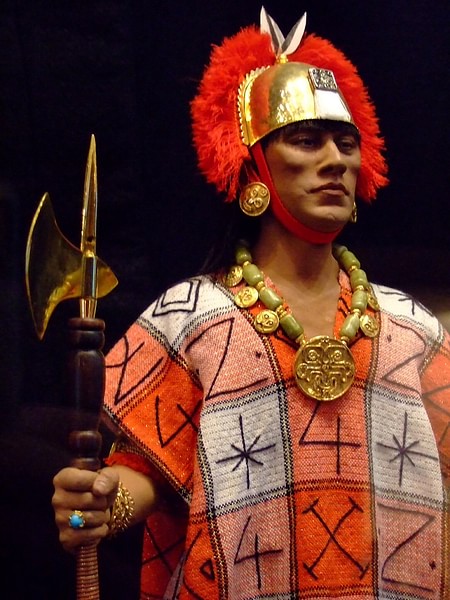

The Incas kept lists of their kings (Sapa Inca) then that we know of such names as Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui (reign c. 1438-63 CE), Thupa Inca Yupanqui (reign c. 1471-93 CE), and Wayna Qhapaq (the last pre-Hispanic ruler, reign c. 1493-1525 CE). It is possible that two kings ruled at the same time and that queens may have had some meaning powers, but the Spanish records are not clear on both points. The Sapa Inca was an accented ruler, and he lived a life of great opulence. Drinking from gold and silvery cups, wearing silver shoes, and living in a palace furnished with the finest textiles, he was pampered to the extreme. He was even looked after following his death, as the Inca mummified their rulers. Stored in the Coricancha temple in Cuzco, the mummies (mallquis) were, in elaborate ceremonies, regularly brought exterior wearing their finest regalia, given offerings of food and drinkable, and 'consulted' for their opinion on pressing land affairs.

Inca rule was, much like their architecture, based on compartmentalised and interlocking units. At the tiptop was the ruler and ten kindred groups of nobles called panaqa. Side by side in line came ten more kindred groups, more distantly related to the king and and then, a 3rd group of nobles not of Inca claret just made Incas as a privilege. At the bottom of the country appliance were locally recruited administrators who oversaw settlements and the smallest Andean population unit of measurement the ayllu, which was a collection of households, typically of related families who worked an area of state, lived together and provided mutual support in times of need. Each ayllu was governed past a small number of nobles or kurakas, a role which could include women.

Local administrators reported to over lxxx regional-level administrators who, in turn, reported to a governor responsible for each quarter of the empire. The four governors reported to the supreme Inca ruler in Cuzco. To ensure loyalty, the heirs of local rulers were also kept as well-kept prisoners at the Inca capital. The almost of import political, religious, and armed forces roles inside the empire were, then, kept in the easily of the Inca elite, called by the Spanish the orejones or 'big ears' because they wore large earspools to betoken their status. To better ensure the command of this aristocracy over their subjects, garrisons dotted the empire, and entirely new administrative centres were built, notably at Tambo Colorado, Huánuco Pampa and Hatun Xauxa.

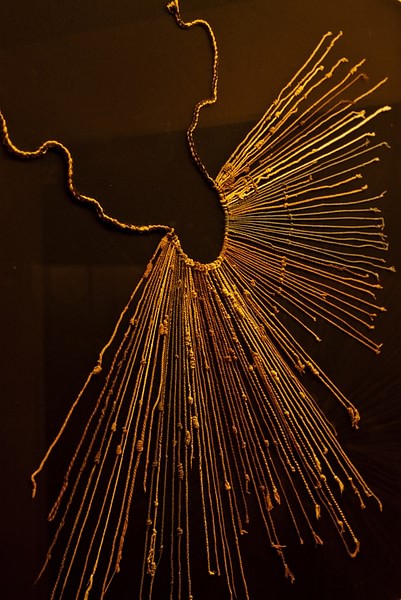

For revenue enhancement purposes, censuses were taken and populations divided up into groups based on multiples of 10 (Inca mathematics was virtually identical to the system we apply today). As there was no currency in the Inca world, taxes were paid in kind - normally foodstuffs, precious metals, textiles, exotic feathers, dyes, and spondylus crush - but also in labourers who could be shifted virtually the empire to be used where they were almost needed, known every bit mit'a service. Agricultural land and herds were divided into three parts: production for the state faith and the gods, for the Inca ruler, and for the farmer's own use. Local communities were besides expected to help build and maintain such purple projects as the route system which stretched across the empire. To keep rail of all these statistics, the Inca used the quipu, a sophisticated assembly of knotted cords which was also highly transportable and could record decimals up to 10,000.

Khipu

Although the Incas imposed their religion and administration on conquered peoples, extracted tribute, and even moved loyal populations (mitmaqs) to better integrate new territories into the empire, Inca culture also brought certain benefits such as food redistribution in times of ecology disaster, better storage facilities for foodstuffs, work via state-sponsored projects, state-sponsored religious feasts, roads, irrigation systems, terrace farms, military assistance, and luxury goods, specially art objects enjoyed past the local aristocracy.

Nigh splendid were the temples congenital in honor of Inti & Mama Kilya - the old was lined with 700 2 kg sheets of beaten gold.

Cuzco

The Inca majuscule of Cuzco (from qosqo, significant 'dried-up lake bed' or perhaps derived from cozco, a particular stone marker in the city) was the religious and authoritative center of the empire and had a population of upwardly to 150,000 at its peak. Dominated by the sacred golden-covered and emerald-studded Coricancha complex (or Temple of the Dominicus), its greatest buildings were credited to Pachacuti. About splendid were the temples built in honour of Inti and Mama Kilya - the former was lined with 700 2 kg sheets of beaten gold, the latter with silvery. The whole capital was laid out in the class of a puma (although some scholars dispute this and have the clarification metaphorically) with the imperial metropolis of Pumachupan forming the tail and the temple complex of Sacsayhuaman (or Saqsawaman) forming the caput. Incorporating vast plazas, parklands, shrines, fountains, and canals, the splendour of Inca Cuzco at present, unfortunately, survives merely in the heart-witness accounts of the start Europeans who marvelled at its architecture and riches.

Inca Organized religion

The Inca had swell reverence for 2 before civilizations who had occupied much the same territory - the Wari and Tiwanaku. Every bit we take seen, the sites of Tiwanaku and Lake Titicaca played an important office in Inca creation myths then were especially revered. Inca rulers made regular pilgrimages to Tiwanaku and the islands of the lake, where two shrines were congenital to Inti the Sun god and supreme Inca deity, and the moon goddess Mama Kilya. Also in the Coricancha complex at Cuzco, these deities were represented past big precious metal artworks which were attended and worshipped by priests and priestesses led by the second well-nigh important person afterward the king: the Loftier Priest of the Lord's day (Willaq Umu). Thus, the faith of the Inca was preoccupied with controlling the natural world and avoiding such disasters every bit earthquake, floods, and drought, which inevitably brought most the natural cycle of change, the turning over of fourth dimension involving death and renewal which the Inca chosen pachakuti.

Sacred sites were also established, often taking advantage of prominent natural features such equally mount tops, caves, and springs. These huacas could exist used to take astronomical observations at specific times of the twelvemonth. Religious ceremonies took place according to the astronomical calendar, specially the movements of the sun, moon, and Galaxy (Mayu). Processions and ceremonies could also exist connected to agriculture, especially the planting and harvesting seasons. Along with Titicaca's Island of the Sunday, the almost sacred Inca site was Pachacamac, a temple metropolis built in honour of the god with the same name, who created humans, plants, and was responsible for earthquakes. A large wooden statue of the god, considered an oracle, brought pilgrims from across the Andes to worship at Pachacamac. Shamans were another important function of Inca religion and were active in every settlement. Cuzco had 475, the most important being the yacarca, the personal counselor to the ruler.

Inca religious rituals also involved ancestor worship every bit seen through the practise of mummification and making offerings to the gods of nutrient, drink, and precious materials. Sacrifices - both animals and humans, including children - were likewise made to pacify and honour the gods and ensure the adept health of the king. The pouring of libations, either water or chicha beer, was also an important office of Inca religious ceremonies.

The Incas imposed their religion on local populations by building their own temples and sacred sites, and they also commandeered sacred relics from conquered peoples and held them in Cuzco. Stored in the Coricancha, they were possibly considered hostages which ensured compliance to the Inca view of the world.

Inca Road Balance Station

Inca Architecture & Roads

Master stonemasons, the Incas constructed large buildings, walls and fortifications using finely-worked blocks - either regular or polygonal - which fitted together so precisely no mortar was needed. With an emphasis on clean lines, trapezoid shapes, and incorporating natural features into these buildings, they have hands withstood the powerful earthquakes which frequently hit the region. The distinctive sloping trapezoid form and fine masonry of Inca buildings were, besides their obvious artful value, likewise used as a recognisable symbol of Inca domination throughout the empire.

1 of the most common Inca buildings was the ubiquitous one-room storage warehouse the qollqa. Built in stone and well-ventilated, they were either round and stored maize or foursquare for potatoes and tubers. The kallanka was a very large hall used for community gatherings. More modest buildings include the kancha - a group of minor single-room and rectangular buildings (wasi and masma) with thatched roofs built around a courtyard enclosed past a loftier wall. The kancha was a typical architectural feature of Inca towns, and the idea was exported to conquered regions. Terracing to maximise land area for agriculture (especially for maize) was another Inca exercise, which they exported wherever they went. These terraces often included canals, as the Incas were expert at diverting h2o, conveying it across great distances, channelling it cloak-and-dagger, and creating spectacular outlets and fountains.

Goods were transported across the empire forth purpose-built roads using llamas and porters (there were no wheeled vehicles). The Inca road network covered over xl,000 km and as well as allowing for the easy move of armies, administrators, and trade goods, information technology was also a very powerful visual symbol of Inca authority over their empire. The roads had rest stations along their way, and at that place was also a relay system of runners (chasquis) who carried messages upwards to 240 km in a single day from one settlement to some other.

Inca Art

Although influenced by the art and techniques of the Chimu civilization, the Incas did create their ain distinctive way which was an instantly recognisable symbol of imperial say-so across the empire. Inca art is all-time seen in highly polished metalwork (in golden - considered the sweat of the sun, argent - considered the tears of the moon, and copper), ceramics, and textiles, with the last beingness considered the most prestigious past the Incas themselves. Designs often use geometrical shapes, are technically accomplished, and standardized. The checkerboard stands out every bit a very popular design. One of the reasons for repeated designs was that pottery and textiles were often produced for the land as a tax, and and so artworks were representative of specific communities and their cultural heritage. Just as today coins and stamps reflect a nation'due south history, so, too, Andean artwork offered recognisable motifs which either represented the specific communities making them or the imposed designs of the ruling Inca class ordering them.

Inca Ruler Atahualpa

Works using precious metals such as discs, jewellery, figures, and everyday objects were fabricated exclusively for Inca nobles, and even some textiles were restricted for their use solitary. Goods made using the super-soft vicuña wool were similarly restricted, and only the Inca ruler could own vicuña herds. Ceramics were for wider apply, and the most common shape was the urpu, a bulbous vessel with a long neck and ii modest handles low on the pot which was used for storing maize. It is notable that the pottery ornamentation, textiles, and architectural sculpture of the Incas did not usually include representations of themselves, their rituals, or such mutual Andean images as monsters and one-half-human, one-half-animal figures.

The Inca produced textiles, ceramics, and metallic sculpture technically superior to any previous Andean culture, and this despite stiff competition from such masters of metal work as the expert craftsmen of the Moche civilization. Just every bit the Inca imposed a political dominance over their conquered subjects, so, as well, with art they imposed standard Inca forms and designs, merely they did permit local traditions to maintain their preferred colours and proportions. Gifted artists such as those from Chan Chan or the Titicaca surface area and women especially skilled at weaving were brought to Cuzco and so that they could produce beautiful things for the Inca rulers.

Plummet

The Inca Empire was founded on, and maintained by, strength, and the ruling Incas were very often unpopular with their subjects (especially in the northern territories), a situation that the Castilian conquerors (conquistadores), led by Francisco Pizarro, would accept full advantage of in the middle decades of the 16th century CE. The Inca Empire, in fact, had still not reached a phase of consolidated maturity when it faced its greatest challenge. Rebellions were rife, and the Incas were engaged in a state of war in Republic of ecuador where a second Inca capital had been established at Quito. Fifty-fifty more serious, the Incas were hit by an epidemic of European diseases, such as smallpox, which had spread from central America even faster than the European invaders themselves, and the wave killed a staggering 65-90% of the population. Such a disease killed Wayna Qhapaq in 1528 CE, and two of his sons, Waskar and Atahualpa, battled in a damaging civil war for control of the empire just when the European treasure-hunters arrived. It was this combination of factors - a perfect storm of rebellion, disease, and invasion - which brought the downfall of the mighty Inca Empire, the largest and richest ever seen in the Americas.

The Inca language Quechua lives on today and is still spoken by some 8 meg people. In that location are too a expert number of buildings, artefacts, and written accounts which have survived the ravages of conquerors, looters, and time. These remains are proportionally few to the vast riches which have been lost, but they remain indisputable witnesses to the wealth, ingenuity, and high cultural achievements of this dandy but short-lived civilization.

This article has been reviewed for accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/Inca_Civilization/

0 Response to "what practice among the moche did the inca adapt to unify its empire"

Post a Comment